This post puts forward a way of thinking about how to run a complex programme, building something that’s never been built before, working across government with a new kind of team.

It presumes a few things are already in place. If they’re not, success is unlikely. These are things anyone running a digital programme worries about:

- the required remit, power, authority and support to make the decisions that need to be made, and implement them

- a team of people with enough time, energy and skills to do the things that really need to be done

- a place to work that can, at least to some extent, be adapted to meet its needs

We’re fortunate in our programme to have enough of each of these to give us a good basis, though at times we’ve really struggled to stretch what we have at the time to make it all work as well as we would like.

Goals, cycles and people

To get a large and complex programme like GOV.UK Verify to work, I think the main task is to manage energy and attention and point them in the right direction and minimise wasted effort.

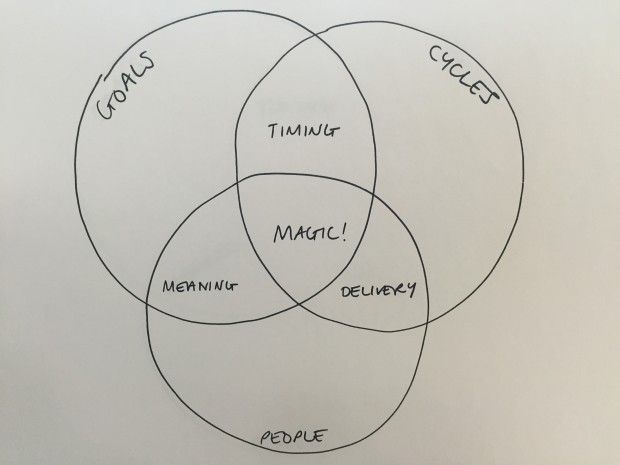

To do that, there are 3 sets of things we need to understand and respond to: goals, people and cycles (inside and outside our team). All these things change over time and they each influence the other more or less at any given time.

Goals

By goals, I mean outcomes that meet user needs, and transform the way users deal with government.

Our big goals are to:

- build and improve GOV.UK Verify to provide a safer, easier, faster way for users to prove their identity online, so they can access services they need

- implement GOV.UK Verify across a range of government services, so that people can have one way to access many services

- grow a new market for identity services in the UK, to meet user needs increasingly effectively while providing a consistently high level of privacy and security

Within these overall goals, we have some more specific goals that we set last March to be achieved by the time we go from beta to live in April.

We also set 3-month programme priorities and goals, and each team has its own goals that capture how they’re going to contribute. Ideally, there’s a link that can easily be traced from our big goals to our yearly objectives, into our 3-month priorities and right down to each story or project the team is working on.

It’s incredibly difficult, when looking across a wide range of functions and responsibilities all working to and within different cycles, to identify relevant, meaningful and actionable goals that work for the whole team.

To do that, you have to understand everything that’s going on in the programme and how it all fits together. Lots of programmes fail to do a thorough job of this and end up setting goals that are seen as irrelevant, meaningless or unachievable.

It’s really worth the hard work. The first time we set programme-wide 3-month goals, it had an immediate and powerful impact. We talked about how to do that, and which bits were most important for us to focus on. We also made a list of things we were *not* going to do over that 3 months - things that are important, but that we're choosing not to prioritise right now.

The sense of direction in the programme immediately and visibly increased, and people said they felt more motivated and more empowered to make decisions within their own remit.

We haven’t perfected this art yet and we probably never will - the important thing is that each time we do it, we learn and improve.

Cycles

As GOV.UK Verify has grown and the team’s range of functions, activities and relationships has increased and become more complex, I’ve found it useful to think about cycles inside and outside the programme and how they relate to and affect each other.

Cycles are periods of time during which things happen. They vary according to their scope, duration, frequency, degree of independence from other cycles, predictability, stability (internally and over time) and the extent to which the people affected by them can control the cycle.

A straightforward discovery or alpha project might only have one main regular cycle that everyone is working to, such as a two-week sprint cycle, situated within the overall lifecycle of a service (as it develops from discovery, through alpha and beta, and into live operation). Even in that context, it can be difficult to coordinate the daily (and sometimes hourly) cycle of essential or urgent maintenance with your fortnightly development cycle. We’ve certainly had to work constantly on this, to try and find the right balance of attention and effort at any given time.

GOV.UK Verify is in the later stages of beta development and heading towards live. We’re taking a market-based approach, and developing a service for implementation across all government services. As such, it includes and is affected by a large number of different cycles of different speed, duration, predictability and intensity. Some are entirely independent from each other, others are closely related to and / or dependent on each other.

A few of the cycles that affect our programme include:

- Parliament (5 years)

- Spending Review (4 years)

- Industry, economic and market cycles (varying length, relevance and intensity)

- Annual budget process (1 year)

- Official procurement exercise for new certified companies (1 year)

- Annual programme business planning (1 year)

- Individual performance management (1 year)

- Programme priorities (3 months)

- Government standards and guidance (updated every 3-6 months)

- Government services developing from alpha, through beta, to live (anything from a couple of months to a couple of years)

- New capabilities being developed in the market and going through the product life cycle (a few months to a few years)

- Technical delivery team sprints (2 weeks)

- software upgrade cycles (various, depending on the software)

- delivery, release and operational cycles

- mob programming team rotation (every 7-10 minutes)

Failing to recognise and respond to the different cycles people are working to and affected by can cause a huge amount of friction and stress. For example, if an agile programme insists on only ever planning 2 or 3 months ahead, it’s unlikely to find favour in a context of 5-yearly spending reviews and annual budget-setting rounds. And if you expect someone running an alpha project to be ready to talk in detail about running their live service at scale, you are probably not going to have a very productive conversation.

It’s not necessary, probably impossible, and likely to be counter-productive, to try to get everyone working to the same cycles or to line up all the cycles so that they are perfectly coordinated. But it’s very important for people to recognise and understand the cycles that they’re working in and those that affect them, and it’s often much more possible and productive than you might think to accommodate difference.

People

It’s obvious that teams involve people, but it’s often forgotten about as an important factor when we think about planning, goals and work cycles. In this instance, I’m talking about people not as units of resource, as is often the case in this kind of conversation, but as humans with all their complexity and unpredictability and weirdness.

Our team includes people from a range of disciplines including designers, developers, communications specialists, operations, user support, content designers, analysts, economists, generalist civil servants, business analysts, researchers, and delivery managers.

We’ve built up our programme from only a few people 4 years ago to more than 70 now. We’ve brought together people from a range of professional disciplines and backgrounds and at various stages of their careers, lives and professional development. We work with a range of people across government, our suppliers and the wider market, all with different expectations, motivations and levels of commitment to and interest in our goals.

When you do that, you have to actively create and nurture your own culture, combining the best everyone who joins the programme can bring into your own unique brand of what it means to be a team working on this particular thing.

What’s important to your team, and what sort of behaviours do you welcome? How are you going to deal with complex decisions, disagreement or disharmony? What stories do you tell each other, what do you stand for, what do you celebrate - who are you, collectively? How are you going to make it safe for people to take risks, make mistakes and learn things? And is that *really* what you want - honestly? (We definitely do, but I’m not pretending that’s a simple or easy road to travel.)

You can’t assume a shared etiquette, language, culture or rules of the game in the way you might in a team that’s been together a long time or that consists of people mainly from the same professional background. Different people in the team might be more or less comfortable with ambiguity, (in)formality, humour, directness, untidiness, pace (or lack of it), slowness, hierarchy (or lack of it).

It’s important to recognise and understand the range of comfort zones you’re dealing with, and work out what the right balance is for your team. And then design goals and work cycles that are going to work in your team.

What it means to align people, goals and cycles

Goals that are meaningful and actionable for people

Having goals that are well-aligned to people means that the people in the team, and your stakeholders, understand the goals and find them relevant and meaningful. Then the goals can be a powerful coordinating, directing and motivating force. If they’re aligned to a person’s remit and sense of responsibility and authority, clear and relevant goals can be empowering, helping people make effective decisions.

Goals that are well-timed and relevant

If you align your goals to the right cycles, you’re more likely to set goals that are relevant to the context and can actually be achieved by the system you’re working in. If your goals aren’t aligned to the right cycles then you might deliver something great, but at the wrong time for it to be useful, at the wrong time in the cycle for you to be able to get funded, or without enough notice for anyone else to plan for your success and benefit from it (or use the thing you’ve built).

Cycles that work for people

Aligning work cycles to people means making it clear to everyone how their work cycles relate to everyone else’s. When a team has goals aligned to its own work cycles, and also understands how its own cycles and goals relate to those of other teams, it can help the team make decisions about what to prioritise, what order to do things in, and how to effectively interact with other teams.

Some signs that you haven’t got your cycles aligned to people:

- if goals are based on a cycle that’s too long, unpredictable, uncontrollable or remote from the cycle someone is directly involved in, then the goals won’t be meaningful to that person and they’re unlikely to provide a useful basis for making decisions

- if the cycles are too rapid, frequent or intense people end up feeling burned out

- if there are too many different uncoordinated cycles to navigate, people can end up feeling lost, confused or disempowered, or end up in disconnected silos, because it’s not clear how what they are doing relates to what everyone else is doing

It’s also really easy to pay too much attention to daily or weekly cycles - meetings taking place, sprints starting and finishing, urgent or unpredicted things arising and getting dealt with. You can get a sense of momentum, camaraderie and achievement from indulging in rapid and frequent cycles while not paying enough attention to longer, less controllable and more abstract cycles that really matter. You need to put in place things to help you all avoid this.

You can’t align all the things all the time

Ideally, you’d have all your goals, people and cycles beautifully aligned all the time. But of course that’s rarely possible.

When it’s working really well and you have proper alignment between your goals, work cycles and people, it’s like magic. You can feel the team working happily, productively and creatively and you can see the results - problems quickly solved, disagreement and conflict easily dealt with, progress swiftly made.

More usually, you can use this model to help diagnose problems and find opportunities for improvement. The valuable thing, for me, is to have a way of diagnosing and responding to issues, and a structured way of making decisions about what to do about them. You can decide to pay more attention to one or more of the sets, and / or one or more of the intersection(s) between the sets, to improve things or solve problems in the programme or in relationships between the programme and the people and organisations we work with.

We’ll be posting more in the next few weeks about some of the things we do to help align people, cycles and goals within GOV.UK Verify. In the meantime, if you’re working on these issues too then I’d be really interested to know how you’re approaching them - please comment below.

4 comments

Comment by Neil Coutts posted on

Great read - love the concept of 'cycles' - particularly the events taking place outside the programme which often have an impact which could be predicted and planned for but so often programmes suffer tunnel vision.

Comment by Simon Terrington posted on

I love this Janet - really interesting and helpful

Comment by Natalie Taylor posted on

We're currently scaling up the no. of teams delivering various aspects of london.gov.uk so I am reading up on the experience of others in this regard. I have found some other useful info in the Service Manual, but also keen to talk to people who have managed to scale-up, whilst being well coordinated and still being agile. Please get in touch.

Comment by Emily Ch'ng posted on

Thanks for your comment. I've emailed you with the relevant details.

Best,

Emily